Continuous sleep is a modern phenomenon and not an evolutionary constant, helping to explain why waking at 3 a.m. is a common experience for many. Understanding this historical context can provide reassurance.

For most of human history, a single, uninterrupted eight-hour sleep was not typical. Instead, people frequently engaged in what is called “first sleep” and “second sleep.” Each period of sleep lasted several hours, separated by a wakeful interval that could last an hour or more during the night. Historical accounts from regions across Europe, Africa, and Asia illustrate how families would retire early at night but wake around midnight for a while before returning to sleep until dawn.

This bifurcated sleep pattern likely altered perceptions of time. The quiet period allowed for a clear division, making the long winter nights feel less monotonous and more manageable.

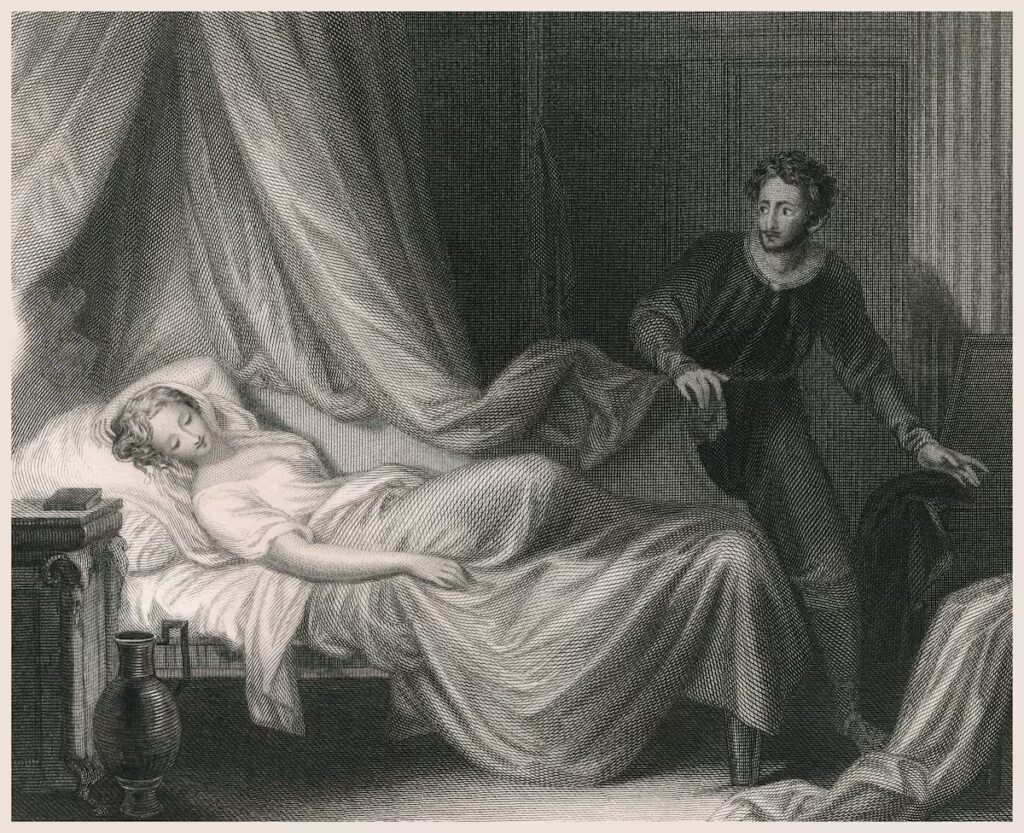

The midnight waking period was not unproductive; rather, it was a time filled with activity. Some individuals would attend to household chores, such as tending to the fire or checking on livestock, while others used the time for prayer or reflecting on dreams. Letters and diaries from pre-industrial societies describe how people used these quiet hours for reading, writing, or even socializing with family and neighbors. This interval was also a time for intimacy among couples.

Literature dating back to ancient Greek poet Homer and Roman poet Virgil references an “hour which terminates the first sleep,” underscoring the prevalence of the two-shift sleep pattern.

Table of Contents

ToggleThe Decline of the ‘Second Sleep'

The transition away from the second sleep occurred predominantly over the last two centuries, influenced by significant societal changes. The advent of artificial lighting played a crucial role. During the 1700s and 1800s, the introduction of oil lamps, gas lighting, and eventually electric lights enabled people to extend their evening activities well into the night, delaying bedtime.

Biologically, exposure to bright light at night altered our internal clocks, or circadian rhythms, making it harder for our bodies to wake after a few hours of sleep. Light exposure prior to bedtime suppresses melatonin, the hormone responsible for signaling sleep, consequently pushing back the onset of sleep.

Moreover, the Industrial Revolution not only transformed work schedules but also redefined sleep patterns. Factory routines favored a continuous block of sleep, leading to a widespread adoption of the concept of eight uninterrupted hours by the early 20th century.

Interestingly, multi-week sleep studies that simulate long, dark winters reveal that participants often revert to a two-sleep model with a calm waking interval. A 2017 study conducted in a Madagascan agricultural community without electricity found that individuals still predominantly slept in two segments, typically rising around midnight.

Long Winters and Time Perception

Light plays a vital role in regulating our internal clocks and can significantly influence our perception of time passing. In winter, the lack of strong morning light makes it challenging to maintain circadian alignment. Morning light is crucial for regulating circadian rhythms due to its high blue light content, which stimulates cortisol production while suppressing melatonin levels.

Research in time-isolation labs and cave studies shows that people can lose track of time when deprived of natural light or clocks. Participants in these studies often miscount the days, indicating how easily time can slip away without visual cues.

This time distortion is especially pronounced during polar winters, where the absence of sunrise and sunset can create a sensation of suspended time. Typically, long-term residents of high latitude areas adapt better to polar light cycles than short-term visitors, depending on community routines. Additionally, a 1993 study of Icelandic populations and their descendants in Canada noted lower occurrences of winter seasonal affective disorder (SAD), suggesting a genetic predisposition to cope with long Arctic winters.

Research from the Environmental Temporal Cognition Lab at Keele University illustrates the connection between light, mood, and time perception. In controlled settings, participants observed clips depicting different lighting conditions and judged time intervals accordingly. Those in low-light conditions perceived time as passing more slowly, particularly if they reported low moods.

Revisiting Insomnia

Sleep experts note that brief awakenings are normal occurrences, often manifesting during transitions between sleep stages, particularly near REM sleep, which is characterized by vivid dreaming. How we respond to such awakenings is crucial.

The brain's perception of time is elastic: anxiety, boredom, and low light can stretch the experience of time, while engagement and relaxation can compress it. When waking at 3 a.m., without the opportunity for a mid-sleep activity or conversation, individuals often fixate on time, making the minutes feel longer.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I) advises leaving the bed after about 20 minutes of wakefulness, engaging in calming activities in dim light, and returning to bed when sleepy.

Sleep professionals recommend covering clocks and minimizing time awareness during sleep struggles. Embracing wakefulness with an understanding of our perception of time may be beneficial for returning to restful sleep.

Darren Rhodes is a lecturer in Cognitive Psychology and the director of the Environmental Temporal Cognition Lab at Keele University.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.